David Schwartz’s daughters never would have discovered their love for the violin, nor would his son have discovered a knack for juggling, if not for a unique in-school enrichment program offered in 129 Israeli municipalities.

Karev, a joint public-private venture founded in 1990, is now the largest extracurricular program in Israel and one of few that operates during school hours. Each participating school chooses three hands-on courses per grade level to be presented three times a week, reaching more than 260,000 preschoolers and primary school pupils.

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

Schwartz’s daughters, now 16 and 18, sampled violin through a Karev class in first grade in their school in Karnei Shomron.

“From second grade on, we paid privately for lessons, but I don’t know if they would have gotten started without getting a taste through Karev,” says Schwartz. “Each of my kids picked up something else.”

Afterschool enrichment clubs are common in Israel, but not all parents can afford the fees or arrange transportation.

“Most extracurricular clubs are after school and it’s kind of informal, for those who have the means to sign up for it,” says Ouri Liberti, Karev district coordinator for Beersheva, Ofakim and the B’nai Shimon region, where school principals tell him that many children lack afterschool alternatives. Karev attempts to bridge gaps across the social board.

“We believe that each student deserves to get enrichment. When we go into a school, all the children get it as part of their school day.”

Having fun activities interspersed through the day has a measurable positive effect on the school environment and on children’s academic performance, according to several internal and independent studies. “If there is math after a Karev dance class, the kids enter math class differently than usual,” explains Liberti. “The Karev classes open their minds and allow them expend some creative energy during the school day.”

It benefits classroom teachers, too. “Sometimes the teachers also participate in the programs, for instance yoga, and that gives them tools to help relax their students in their regular classroom,” says Liberti.

Flexible curriculum

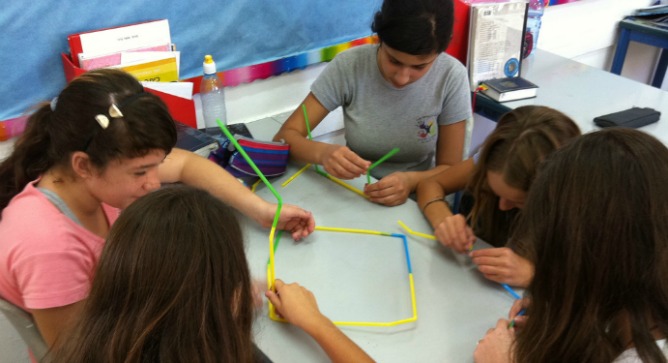

One of the unusual aspects of Karev is the degree of choice each school enjoys. Every year, a committee composed of educational staff and parents chooses from a broad range of options for each grade — for example, drama, origami and gardening for first and second grade; bird-watching, cooking and electronics for third and fourth grade; and comics, robotics and social activism for fifth- and sixth-graders.

“The program provides educational opportunities to various sectors in Israeli society, from the Golan [in the north] to Eilat [in the south], including students in the periphery, children at risk, children with special needs, immigrant children and children in Arab, Bedouin and ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities,” says Liberti.

“Our pedagogical division works to make our programs suitable to specific populations. In the case of Arab kids, the program has to be translated and adjusted to the culture.” There are 36,000 Arab-Israeli children involved in Karev currently.

Teachers for the different classes are hired from the local population whenever possible. In fact, one goal of the initiative is to provide jobs for people with expertise in various disciplines that aren’t part of the normal curriculum.

Liberti explains that Karev was founded by Canadian philanthropists Charles and Andrea Bronfman in reaction to education budget cuts in the late 1980s. Their aim was not only to put back arts and other extracurricular subjects into the school day to complement what’s available in classrooms, but also to reemploy laid-off teachers in art, music and other subjects.

The program was successfully piloted in Jerusalem and Beit Shemesh, and two years later the Ministry of Education began providing the budget to expand the program.

Today, the bulk of the costs are shared by the ministry and the participating municipalities. Parents pay on a sliding scale, averaging about NIS 200 per year for three classes. Liberti points out that in the private sector, afterschool enrichment costs that much for just one subject per month.

“Initially, Karev was aimed at needy populations, but then many wealthier municipalities liked this program and were willing to pay more to bring it in,” Liberti adds. “Our vision is that all students in Israel will be included in this program, because it’s worthwhile.”