Tending terminally ill Bedouins in the Negev desert is not a popular medical specialty, to say the least. But Dr. Yoram Singer was raised to believe in equality among people. His European parents also taught him that “if you want to do something, you can always find a way to do it,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

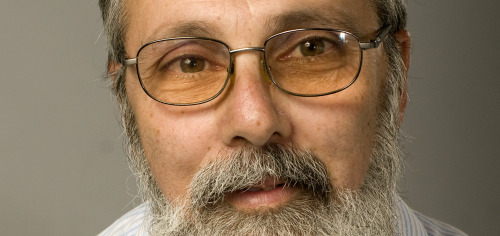

Late last year, Singer received an award from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in recognition for his twice-weekly “house calls” to the tents and shacks in unrecognized Bedouin villages. The medical director of the Home Palliative Care Unit of the Clalit Health Services health fund and chairman of the Israeli Association of Palliative Care, Singer was described at the award ceremony as “an angel of mercy.”

“I think an important part of being an adult is helping the helpless, trying to do something in places where there is nothing,” Singer tells ISRAEL21c.

Singer was born in Canada in 1953, grew up in Switzerland and immigrated on his own to Israel after high school. He began his career in palliative care, which aims to alleviate symptoms and improve the quality of life for chronically or terminally ill patients, in 1991, when he was invited to head the newly founded palliative care unit at Ben-Gurion University’s Faculty of Health Sciences in partnership with the Israel Cancer Association and Clalit Health Services.

More than a one-man show

Singer estimates that throughout Israel, no more than 15 percent of those needing palliative end-of-life care actually receive it. His ambition is to build up a larger and more comprehensive network of services, including inpatient hospice units.

Through his involvement in course development and research at Ben-Gurion University’s medical school, Singer introduced palliative care to the family residency-training curriculum. To expand his own knowledge, Singer did a palliative care fellowship in his native Montreal from 1995 to 1996.

He now oversees homecare hospices in Kiryat Gat and in Rahat, the largest Bedouin city in Israel. Five years ago, the program rolled out a Mobile Palliative Care Unit (MPCU) to serve Bedouins and Jews living in remote areas. In addition to his regular clinic hours, Singer serves on the MPCU twice a week.

The main target population of about 180,000 Bedouin Muslims is spread out over six townships and isolated, primitive transitory encampments. Home visits are conducted by the mobile unit’s rotating team of nurses, social workers, physicians (Jewish and Bedouin) and Bedouin driver-translators.

“It’s not a one-man show; I could never do something like this myself,” stresses Singer, who relaxes with his gardening and photography or by traveling round the world.

We should “concentrate on our commonalities”

Singer notes that Bedouin Muslim patients do not balk at being treated by Jewish doctors, nor do Jews mind being treated by Arab doctors.

Dying people, regardless of culture, geography or socio-economic conditions, experience similar emotions: “The sadness of departing, the fear – not really of death, but of what’s going to happen on the way – and an urge to close circles, to say goodbye and to forgive. All these are quite universal. And if we could concentrate on our commonalities more than our differences, we would be much better off,” says Singer.

His conviction that each of us has a personal responsibility to help the helpless led Singer to spend two years at a Swiss Protestant mission hospital in southern Africa, after earning his medical degree from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1982.

“People thought I was crazy,” he recalls. He worked in a 500-bed hospital where each bed was normally shared by two patients. “I did a lot of community health development and food projects; there was a lot of malnutrition there, and children were dying of hunger,” he says.

He and his wife, a music teacher who now practices alternative medicine, returned to Israel and settled in the southern city of Beersheba, the Negev’s unofficial capital. They have raised their four children there. Both before and following his appointment as head of the Home Palliative Care Unit, Singer cared for poor patients in a nearby development town as a family physician.