In the war on cancer, Israeli research could have a major impact courtesy of the Israel Cancer Research Foundation, which is handing out seven-year grants to Israeli scientists working in this field. Since it was founded in 1975, 1,600 Israeli labs have won grants, leading to a number of promising new drugs and breakthroughs in research.

The war against cancer is fought daily by hundreds of thousands of “soldiers” – doctors, nurses, technicians and researchers who treat patients and spend long hours in labs around the world. Nonetheless, cancer is still winning. It is responsible for one in four deaths in Western countries, and the mortality rate for major malignancies has remained almost steady for the past half century.

But recent discoveries in molecular biology have brought greater understanding of how some genes mutate and are involved in cells becoming cancerous, while others inhibit cancer cells. Such research has already produced drugs that fight cancer better than surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy alone, and there is hope for even better treatments and even cures.

Prof. Yashar Hirshaut, chairman of New York’s Israel Cancer Research Foundation (ICRF) and a senior oncologist at the Weill-Cornell Medical College-New York Hospital, hopes that when the war is won, Israelis will have played a prominent part.

The ICRF, a voluntary organization funded by private donations, was founded in 1975 by the late Dr. Daniel Miller, then head of the lymphoma clinic at Manhattan’s Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center where Hirshaut was then working. He and a group of American and Canadian researchers, oncologists and lay people were determined to harness Israel’s educational and scientific resources in the fight against cancer.

Initially, it aimed at stemming the “brain drain” of Israeli researchers by supplying funds for postdoctoral fellowships in the US for young PhDs, but then it switched to become the only US-based charity solely devoted to financing Israeli cancer research. It has raised more than $33 million in the form of seven-year grants of $50,000 a year. Fellowship recipients from 1,600 labs have been selected on the basis of merit after a rigorous peer-review process conducted by world-class experts in disciplines related to cancer.

“An ICRF grant is such a wonderful fellowship,” said immunology Prof. Yehudit Bergman, who is among the 50 Israelis on the 2008 list, in an interview at the Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School where she works. “It gives you peace of mind that you have seven whole years to produce a nice piece of work. Most grants we researchers get are shorter, like four years, and we never have security. Biology research is so expensive due to the cost of lab animals and technology.”

Among the other 49 Israelis to receive professorships, clinical research career development awards, post-doctoral fellowships or project grants are Nobel Prize laureates Prof. Avram Hershko and Prof. Aaron Ciechanover of the Technion Israel Institute of Technology, and, for the third time in a row, HU-Hadassah Medical School Prof. Howard Cedar, an Israel Prize laureate who has just been selected to share the $100,000 Wolf Prize in Medicine for 2008.

Hirshaut said in an interview that ICRF makes it possible for scientists to use Israel’s “unique population of diverse ethnic groups to study genetic and environmental data that contribute to cancer. It also places a strong emphasis on young scientists with fresh approaches to areas that have challenged the experts, and draws on the country’s unparalleled convergence of some of the finest scientists and physicians in the free world.”

ICRF fellows have already had numerous successes: Velcade, a multiple myeloma drug, was based on Hershko and Ciechanover’s discovery of the ubiquitin system. Gleevec, the first drug to directly target cancer cells, was developed based on the work of Dr. Eli Canaani of the Weizmann Institute. Doxil, the first drug encapsulated in a liposome for direct delivery to a tumor site, was developed by HU Prof. Yechezkel Barenholz and Prof. Alberto Gabizon of Shaare Zedek Medical Center. Cedar has done pioneering, world-class work on DNA methylation, a molecular process that turns genes on and off. The role of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in the majority of human cancers was elucidated by ICRF awardees Dr. Moshe Oren and Prof. Varda Rotter of the Weizmann Institute. Prof. Ephrat Levy-Lahad of Shaare Zedek discovered that a minor mutation in the RAD51 gene increases the risk of breast cancer in women with the BRCA2 gene mutation. And a novel bone marrow transplant technique was developed by Prof. Yair Reisner of the Weizmann, who thus greatly expanded the donor pool for leukemia treatment.

Hirshaut, who was born in Berlin and fled the Nazis with his family to Japanese-occupied Philippines, first visited Israel as a child in 1949 and graduated from Yeshiva University’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine. He has a personal reason for being interested in cancer: His father, an accountant, died in New York after contracting a rare type of throat cancer, apparently caused by a virus in Southeast Asia. Just before he died, “a doctor told my mother he would die shortly,” recalled Hirshaut, who was then 19. “I lived with that knowledge less than two weeks, but it was hell on earth.”

When he was a young Sloan-Kettering oncologist who had learned the specialty at the US National Cancer Institute, all the known cancer drugs were stored in one glass cabinet there. Now there are many more options. He said he has witnessed the transition from yesterday’s very primitive field to one where cancer patients have many more chances to survive.

Even in those early years, said Hirshaut, “a cure was becoming available for Hodgkin’s disease and lymphoma, and researchers were trying to prove that some cancers result from viruses. There was the determination of a few people – almost like the Zionist dream – that if you will it, it could be achieved. But instead of treatments being discovered by chance, cancer research today is much more focused on molecular biology. We increasingly will be able to identify cells’ growth pathways and customize drugs to treat patients according to their genetic makeup and the kind and stage of cancer.”

The ICRF chairman, who is an Orthodox Jew, noted that most donors are North Americans Jews and Israelis, but some generous donations have come from non-Jews as well. Quite a few donors have had cancer in their families. The donors are matched with identified researchers. “We arrange for them to meet their scientist. It is an exciting event for both sides.”

Some $6 billion is spent annually in the US on cancer research, while the amount in Israel is less than $10 million, with about $1.6 million coming from the ICRF. “When we support someone, they are creating their own ideas. They get credit for their own work, and are not just part of an anonymous team. Their fellowships help them climb the academic ladder,” pointed out Hirshaut, whose Random House book for the layman, Breast Cancer: The Complete Guide, is about to go into its fifth edition. “We have revised it every four years, as the field is changing a lot, especially regarding chemotherapy and hormone therapy. Doctors didn’t think in the past about treating recurrences, because most women died from a first bout, but now there are treatments even for returning breast cancer.”

Cedar (the name was changed by his grandfather from Siddur, or prayer book), was born in the US in 1943, graduated from medical school and received his Ph.D. from New York University in 1970. After doing research at the US National Institutes of Health, the observant Cedar came on aliya with his wife Tzippi (a psychodrama expert) and their children, and has been at Jerusalem medical school’s department of cellular biochemistry and human genetics ever since. His son Joseph Cedar was director of the award-winning Israeli film Beaufort, and a movie poster hangs outside Howard’s office.

The professor’s work (with Yehudit Bergman and others) on DNA methylation (chemical changes in the DNA molecule) is a very basic aspect of animal cell biology. This molecular process turns on and off the approximately 40,000 genes in everyone’s body. Cedar explained that everyone inherits genetic information, but that it “has to be used in a programmed manner. That programming is called epigenetics. The older one gets, the more likely the programming mechanism is to make mistakes. One thing that these changes in epigenetics control could predispose a person to cancer. That would explain why cancer is largely a disease of old age,” said Cedar, whose methylation work is considered by some to be worthy of a Nobel Prize.

“In only five percent of cancer cases, methylation is not involved,” he said. “The drug industry today is now heading toward customized treatment. I think methylation is the next stage, as it is common to almost every tumor. If you can find a way to prevent it, you will get a bigger bang for your buck.”

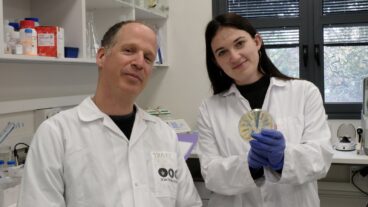

Bergman, whose husband teaches at the HU’s School of Business and has two grown children, was very excited when she won her ICRF grant. “I am trying to understand mechanisms during tumor genesis that silence genes inappropriately.” As she works on mice, she is at her lab daily for about 12 hours and sometimes on weekends.

One of her achievements is discovering that when a single cell makes an antibody, it involves a special mechanism in which only one allele of a gene pair is chosen. This mechanism, added Cedar, “is certainly involved in cancer. We hope to understand the processes involved in gene silencing, and how to prevent it from happening. We also want to be able to follow the processes prior to cancer as a screening possibility.”

Cedar and Bergman agree that research is like exploring for new continents, or like a detective on a case. They explore a tiny universe inside the cell. Bergman added: “You need to be optimistic and have a lot of patience to be a researcher, as science has lots of ups and downs. Even if an experiment fails, you learn more about nature, and that can lead to something else.”

Cedar says young Israeli biology researchers are probably the best in the world. Perhaps, he suggested, physicians need immediate gratification by making people better every day, while researchers can wait a long time. But Cedar is worried about whether there will be enough bright and motivated young researchers in the future, as business and computers attract some of the best. He also favors encouraging more women to enter the field.

But the most important task, said Cedar, is for the government to invest more in basic research. “Society has to understand that the best way to use its resources is to put them into basic research. We can’t import this knowledge from abroad. Even in economic terms, putting resources into basic science has the greatest effect on society.”

Printed by courtesy of The Jerusalem Post.![]()

Slashdot It!![]()