For millions of women worldwide facing premature ovarian failure rendering them unfertile, results of a new study in Israel provide some concrete hope.

A team of Israeli scientists have successfully transplanted whole frozen and thawed ovaries in sheep, retrieved oocytes from these ovaries and triggered them in the laboratory into early embryonic development.

According to a report in the journal Human Reproduction, follow-up tests showed that the ovaries in the two sheep from which oocytes were recovered were still functioning normally three years later.

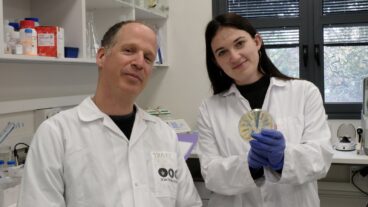

The study’s lead author Dr Amir Arav, senior scientist at the Institute of Animal Science, Agriculture Research Organization, at Bet Dagan, said that the results demonstrate for the first time that it is possible in a large animal species, to remove, freeze, thaw and replace ovaries, obtain oocytes and maintain normal ovarian long-term function.

This holds out hope that this approach could become a feasible treatment for women facing premature ovarian failure, and furthermore, that the advances they have demonstrated that new freezing techniques may have potential for other human organ transplants, which are currently done using only fresh grafts.

Co-author Yehudit Nathan, program manager at Core Dynamics, the biotech company that funded and provided the scientific and technological expertise for the project, said the next goal was to attempt to transplant ovaries in women at risk of losing their fertility.

“There is a lot of research still to be done, but we hope that it will not take more than a few years for this to become a practicable option for women, such as young cancer patients, who would otherwise be left infertile after their treatment,” she told Medical News Today.

Whole ovary autologous transplants have already been attempted twice in women – in 1987 and 2004 – in both cases into the upper arm, but in neither case was the ovary frozen and thawed first.

Another much-researched option is freezing and transplanting thawed ovarian tissue. Two babies have been born using this technique. However, adhesions and the loss of blood to the ovarian follicles that occurs during the interval before new blood vessels are being formed, remain major obstacles.

The first aim of the Israeli team was to test in vitro whether whole ovaries from sheep, together with the blood vessels, could survive the freeze-thaw process using a technique they have developed that allows precise control over the propagation of ice crystals during the freezing process, thus reducing the damage caused to cells by conventional methods. Sheep were chosen because their ovaries are similar to those of humans. The technique worked – the frozen-thawed ovaries produced comparable numbers of follicles as the fresh control ovaries.

The next objective was to see if they could remove, freeze and thaw the right ovary from eight sheep, including the vascular pedicles (the attachment that contains the main blood vessels), and replace the ovary up to a fortnight later, either at the original site or by grafting it on to the pedicle of the (removed) left ovary. Of the five sheep where normal blood flow resumed immediately, indicating that the transplant had succeeded, one had severe adhesions and it was not possible to attempt oocyte collection, but two yielded one oocyte each and repeat aspiration four months later produced four more oocytes from one of these sheep.

All six ooctyes were activated parthenogenically using chemicals that mimic the normal fertilization process, and developed into 8-cell embryos.

“We used parthenogenic activation as we had only a low number of oocytes and because IVF success in sheep depends on the quality of the ram’s sperm. This way, we knew that the development of the embryo depended solely on the quality of the ooctye,” said Arav.

Two years after transplantation the researchers carried out magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on one sheep with a transplanted ovary and one untreated control sheep. It showed that the transplanted ovary contained small oocyte follicles, and although a little smaller than the ovary in the control sheep it was within the normal range. The blood vessels were also intact.

“This approach could revolutionize the field of cryopreservation for diverse human applications, such as organ transplants, as well as helping women who face the loss of their fertility,” said Arav.