A model of psoriasis cells – a molecule called Fas acts as a middleman between activated immune cells and a handful of inflammatory hormones involved in psoriasis flare-ups.An immune molecule that normally assists in cell ‘suicide’ may be an important trigger in the development of the common skin disease psoriasis, according to scientists from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology and State University of New York, Stony Brook.

According to the National Psoriasis Foundation in the United States, one to three percent of the world’s population suffers from psoriasis. About 30 percent of people with psoriasis have severe cases, where the affected skin covers more than 3 percent of their body. In some people, the disease is associated with a form of arthritis.

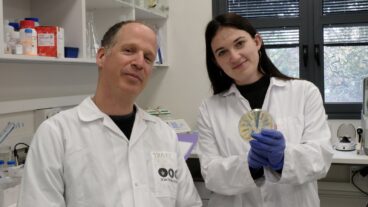

The culprit, a molecule called Fas, acts as a middleman between activated immune cells and a handful of inflammatory hormones involved in psoriasis flare-ups, say Technion researcher Dr. Amos Gilhar and colleagues. The study appears in the January American Journal of Pathology.

Psoriasis is a non-contagious, lifelong skin disease that usually appears as scaly and inflamed patches of skin, although it can take several different forms. In patients with psoriasis, the white blood cells that make up the body?s immune defense system go into overdrive, triggering other immune responses that pile up skin cells at an abnormal rate.

Current treatments for psoriasis such as the drug Enbrel focus on these inflammatory hormones, but the researchers were able to stop the development of psoriasis in mice long before these hormones came into play by injecting an Fas-blocking antibody.

“The finding that antibodies to Fas can prevent psoriasis further demonstrates the complexity of the disease and its numerous molecular pathways,” Gilhar says.

Dr. Alice Gottlieb, chair of the Clinical Research Center at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Jersey agrees. “This research shows that activation of the Fas pathway is important in starting the ball rolling in psoriasis,” comments Gottlieb (who was not involved with this study). “These findings could have implications for other immune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease.”

The researchers suspected that the Fas molecule was in the middle of this process, since it is found at high levels in psoriatic skin and leads an intriguing dual life. Most of the time, Fas guides the normal process of cell suicide called apoptosis. But in cells where apoptosis is blocked by other molecules, as it is in psoriatic cells, Fas switches roles and encourages the production of common inflammatory hormones instead.

To figure out exactly where Fas stood in the development of psoriasis, Gilhar and colleagues transferred grafts of clear, non-involved skin from human psoriasis patients to mice. They injected the mice with white blood cells bearing the Fas molecule on their surfaces to jump-start the formation of psoriatic skin lesions.

By blocking Fas action with a special antibody, the researchers were able to show that Fas actually is the key middleman in psoriasis formation. Without Fas, the natural killer cells were unable to trigger the production of the inflammatory hormones that lead to the characteristic skin thickening and other signs of psoriasis.

There is some evidence that Fas is involved in other skin conditions such as eczema, so future treatments targeting the Fas pathway may prove useful for a variety of diseases, suggests Dr. Richard Kalish, Gilhar’s collaborator from SUNY Stony Brook. However, researchers need to develop a human antibody to Fas before the technique could be tested in people.

“The current study is one of the many wonderful papers that have come out of this very productive collaboration across many miles between Dr. Gilhar and Dr. Kalish,” says Gottlieb.