Dining in a restaurant in Jaffa, Tel Aviv mosaic artist Audrey Meyer-Munz noticed a crack in one of the patterned china plates she was served on. “I pointed it out to the waiter and asked if I could take it, if it couldn’t be used anymore,” says Meyer-Munz. “They gave it to me. Now it’s in one of my works.”

Mosaics, common forms of decoration in the ancient Mediterranean region, have become a modern Israeli medium to brighten public spaces and recycle bright, colorful bits and pieces of stone, glass and tile headed to the trash heap.

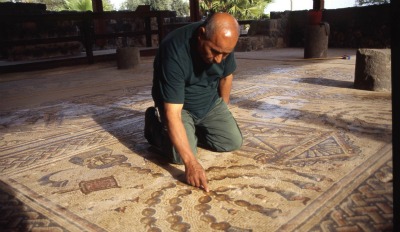

From intricate mosaic floors uncovered in Roman-era synagogues in northern Israel, to the Marc Chagall wall mosaic decorating Israel’s Knesset building, this is an art form perfect for places kissed by the sun nearly all year long.

“The Mediterranean basin is where mosaic art has bloomed and flourished,” says Meyer-Munz, who emigrated from Belgium 25 years ago. “I’m not sure how I would have been as a mosaic artist in Belgium, where it is rainy and gray. Here we have light that I have expressed over and over again in the vivid colors I use. There is something very special with the light here in Israel.”

Yael Nitzan, co-founder of the Organization of Israeli Mosaic Artists (OIMA) established in 2006, says the group includes 250 members and counting.

“I’m in the middle of a new book about mosaics in the public spaces of Israel,” she tells ISRAEL21c. “There are about 200 murals and 110 sculptures incorporating modern mosaics throughout Israel, including a 13-square-meter mosaic in Kfar Adumim in the center of town.”

The nearby Museum of the Good Samaritan opened in 2009 as Israel’s first mosaic museum and one of only three worldwide.

And in October last year, an International Mosaic Festival in Netanya offered four days of workshops, exhibitions, an academic conference and two communal projects: the completion of the world’s largest mosaic comprised of discarded socks, and a mosaic wall made by children (with professional guidance) at the Netanya Museum.

Bringing a colorful art form back to life

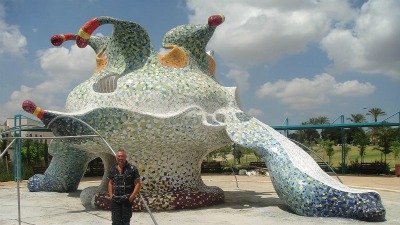

The revival of mosaic art (p’sayfas in Hebrew) is similar to the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language, says Igor Sarni, manager for the Jerusalem studio of Ruslan Sergeev, one of Israel’s foremost mosaic sculptors.

“Just as [Eliezer] Ben-Yehuda began reviving Hebrew 100 years ago, the Catalan architect [Antoni] Gaudi began using broken mosaic tiles to decorate the outsides of his Barcelona buildings at the end of the 19th century,” Sarni relates. “Today, Ruslan is continuing this tradition. In Israel, people used mosaics since Roman times because the colors remain lively over the years to enjoy.”

Sergeev, who moved to Israel in 1996 from Belarus, works with leading architects and Israel’s ministries of housing and tourism to produce award-winning landscape sculptures — he calls them “bio-art” — at his Jerusalem studio. His work is displayed also in England, the United States and Russia, and he was one of two Israelis invited to exhibit at the first and second annual International Festivals in Contemporary Mosaics in Ravenna, Italy, in 2010 and 2011. The other was Ashkelon mosaic artist Ilana Shafir.

Among more than 90 whimsical Sergeev creations are giant birds and eggs at an industrial park in Netanya, jellyfish and coral climbing structures in Eilat’s Garden of the Senses, and wheelchair-accessible play structures at a government-planned Kings Forest playground for disabled children near Kiryat Gat.

The ceramic and mirror pieces that face his jumbo sculptures are gathered from Israeli building renovation sites and old, crumbling mosaics.

“The materials must be very strong because the sun is very hot in Israel,” Sarni explains to ISRAEL21c.

Rising dramatically above the Dead Sea in Ein Tamar, the first mosaic sculpture by modernist artist Jo Jo Ohayon incorporates materials he collected in Tel Aviv, Beersheva and Haifa. He says he chose this medium “because I can use many colors and it will last outside for 1,000 years under the sun. No other material will last like that.”

Mosaics tell stories

While many of Israel’s mosaic works are abstract, many others cohere into pictures that tell a story.

“The Twelve Mosaics,” decorating the fountain in front of Tel Aviv’s Old City Hall at Bialik Square, shows the history of Tel Aviv-Jaffa over 4,000 years. These mosaics are the work of the late Nahum Gutman, an Israeli painter, sculptor and author who emigrated from the Russian Empire in 1905.

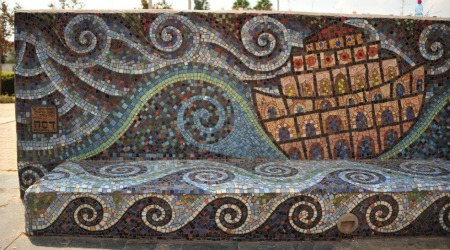

Yoav Dassa’s 18-meter-long sitting area in Ganei Tikvah uses a ceramic tile and natural stone mosaic to depict scenes from the Noah’s ark narrative. Dassa also worked with residents of Ahava Children and Youth Village in Kiryat Bialik to create several mosaic mirrors that now hang throughout the refuge for abused children.

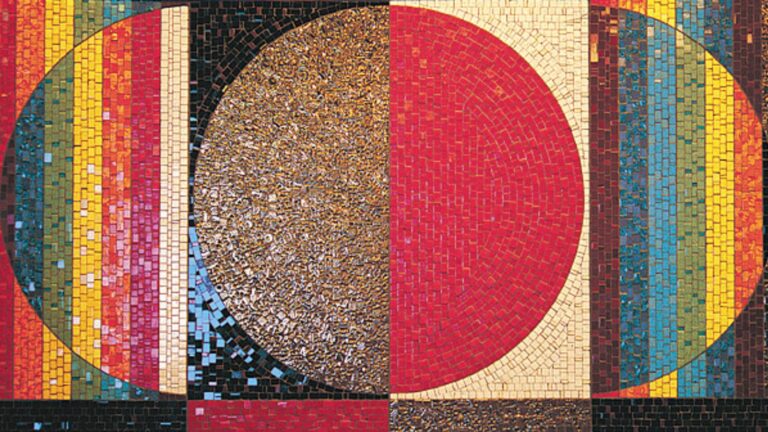

Meyer-Munz terms her works “picto-mosaics” because they’re done on a board meant to hang on a wall. She gets her refined and organic stones and gold-and-silver-pigmented glass smalti tiles from Italy, as well as beads, precious stones and tiles from Tel Aviv’s craft shops and kitchen-bath shops.

After falling in love with mosaic arts in Israel, she took lessons for two years and then set up her own studio in early 2005. “I do portraits of people, landscapes and things that come from my imagination. Sometimes I do theme work for exhibitions in Israel and abroad.”

In 2007, she was invited by the Biennale of Florence to display her creations along with paintings, sculptures, video installations and other types of art. “Out of almost 800 participants there were only four mosaic artists, each from different countries and having different techniques,” she says.

Meyer-Munz recently won second prize in applied art at the Biennale of Chianciano in Tuscany, where 160 artists from 50 nations were selected among 1,600 applicants. “I was the sole mosaic artist, although not the only Israeli,” she says.

“I know that countries like Israel and Italy, even Arabic countries, are very interested in mosaic art. But it is not recognized as highly as photography and other types of art, and I want to change that.”

And if you accidentally shatter a colorful piece of ceramic, don’t throw it out. “I joke that whenever there’s a fight at home and you break plates and vases, please save all the shards for me,” says the artist with a laugh.